I taught tenth grade for a long time. Part of the curriculum for that level in the state of Georgia is to cover the Holocaust, a tough topic no matter where you live. Here in the South, discussion of any type of racial or cultural discrimination inevitably leads to discussion of the legacy human slavery has left in our backyards. As Oprah pointed out in an interview with Elie Wiesel, survivor of Auschwitz and author of Night, we don’t compare our pain, and the heartbreak of the concentration camps can’t be held against the heartbreak of African slavery in the 19th century, but they both beg the question, according to Wiesel, “What is there in evil that becomes so seductive to some people?”

Heavy stuff for a sewing blog, I know, but I promise that I’ll bring it all back around.

When I was teaching this topic, I used materials provided for free by the Southern Poverty Law Center, whose mission is to combat hate, intolerance and discrimination through education and litigation. They not only include primary documents related to the Holocaust and to the Civil Rights movement in the American South, but also the Japanese internment camps in the United States during the second World War.

The who in the what? I had no idea what that was. Japanese internment? Like, concentration camps? IN AMERICA?

Yes. In America. And this year during spring break, my husband and my children and I visited the most famous of them: Manzanar.

You may not think you’ve heard of Manzanar, but you have. If you watched the original Karate Kid, you saw Miyagi mourning the death of his wife and son–the telegram tells him they died at Manzanar. If you loved the original Star Trek, you are familiar with Lieutenant Sulu, played by George Takei--who spent a part of his childhood living at Rohwer, another camp similar to Manzanar. If you’re younger, in the past fifteen years you may have read a young adult novel called Farewell to Manzanar, about the experiences of children living there.

It’s a hard story to tell. Fearful that Japanese living in America would feel greater allegiance to the Emperor of Japan than to their adopted nation, the United States government made the decision to centralize Japanese-American citizens in camps like Manzanar for their protection. The argument was that they were a security risk, and so the entire West Coast was made off-limits for anyone with Japanese ancestry, including both issei (those who were born in Japan and emigrated to the US, and who may or may not have obtained citizenship) and the nissei (those of Japanese ancestry who were born in the US, and were by definition all American citizens).

The area of California set aside for Manzanar, west of Death Valley but east of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, is breathtakingly beautiful. The mountains rise 6000+ feet above the valley floor, and the wind whips the snow from their peaks with a constant, tugging power. The wind, the wind, the wind there never, ever dies. It is an all-encompassing presence at Manzanar, as real as the buildings and the sandy soil that gets into every crack. This is desert country, with desolate stretches that seem devoid of all life. It is not a hospitable place to live.

At the time of the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, approximately 120,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry were living in the United States. In a nation already rife with racial prejudice, the Japanese community found itself under concerted efforts to isolate and eradicate them. Although many were born on US soil and fully citizens, processes were put in place to move all Japanese Americans away from the “military areas,” in this case defined as those parts of the country closest to Japan and thus at greatest risk from spies and Japanese on US soil loyal to the Emperor. This included the entire west coast, from Southern California to Washington state.

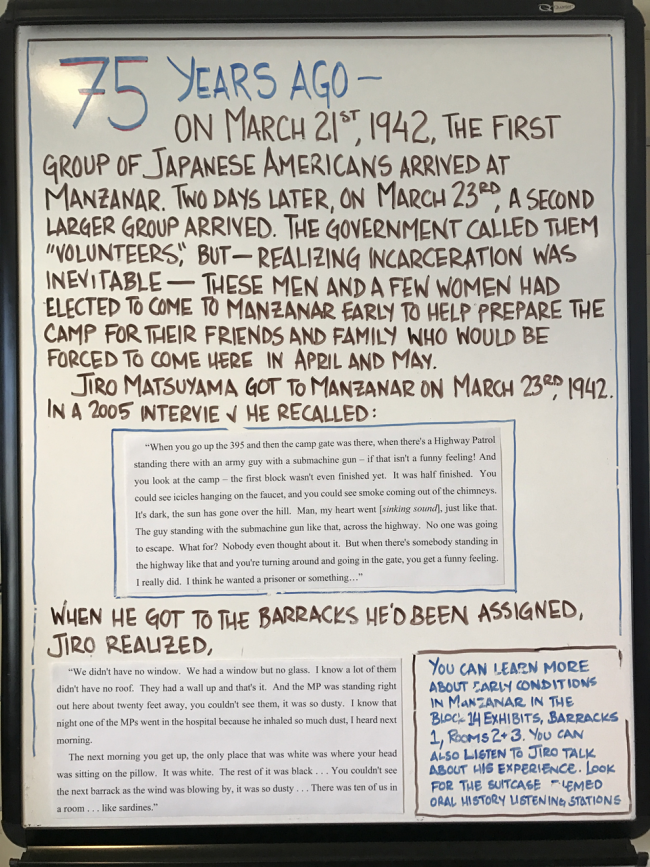

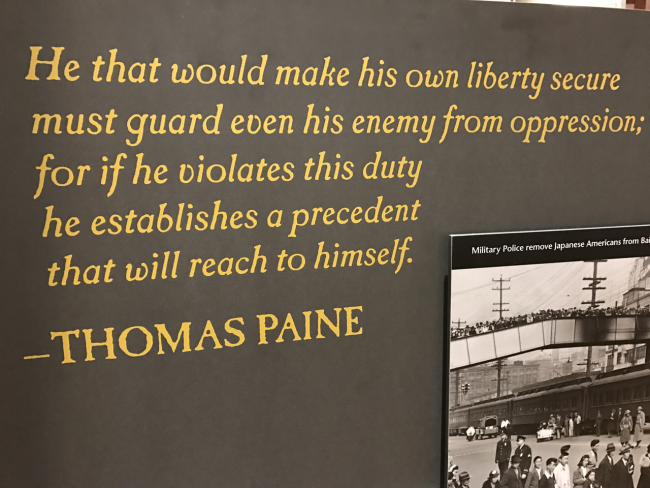

In February 1942, with the US fully at war with Japan, Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, and while it was not specifically worded with this intent, it authorized the removal of all individuals of Japanese ancestry, both immigrants and born citizens, away from Military Areas and to neutral territories–mostly to the central United States. The camp at Manzanar was one of these evacuation areas. Called internment areas or relocation centers, they were for all intents and purposes concentration camps for American citizens, on American soil.

It is a breathtaking place. The air whips around you, the mountains tower over you, and the desert sand flies ahead of you as you walk the trails that were built by the hands of individuals who had only days to gather their worldly possessions, load onto buses with their families, and arrive at a destination where they knew nothing and no one, where even the buildings to house them had not yet been constructed. The barracks would be built by their own hands after their arrival.

It is a breathtaking place. The air whips around you, the mountains tower over you, and the desert sand flies ahead of you as you walk the trails that were built by the hands of individuals who had only days to gather their worldly possessions, load onto buses with their families, and arrive at a destination where they knew nothing and no one, where even the buildings to house them had not yet been constructed. The barracks would be built by their own hands after their arrival.

Left behind were businesses and homes, no longer considered the property of these individuals who had been denied due process and rights to citizenship. When they returned, there would be nothing left. The families were assigned registration numbers, their belongings were catalogued and confiscated, and by November of 1942, the relocation was complete and all those with Japanese ancestry had been transported to one of ten camps east of California.

It is the reaction of this community that most astonishes me about this place. They arrived at one of the most desolate and lonely locations I have ever encountered, surrounded by high fences and barbed wire–not that it mattered, because they were hemmed in by the desert and the mountains and they had nowhere to go. In this place, they built gardens and ponds, homes and workplaces, cemeteries and hospitals. The signs still stand at the National Site to mark where they would send their children to school over the coming years, where they would hold sock hops and weddings, where they would bury their dead and mourn their losses, celebrate victories and fight for peace.

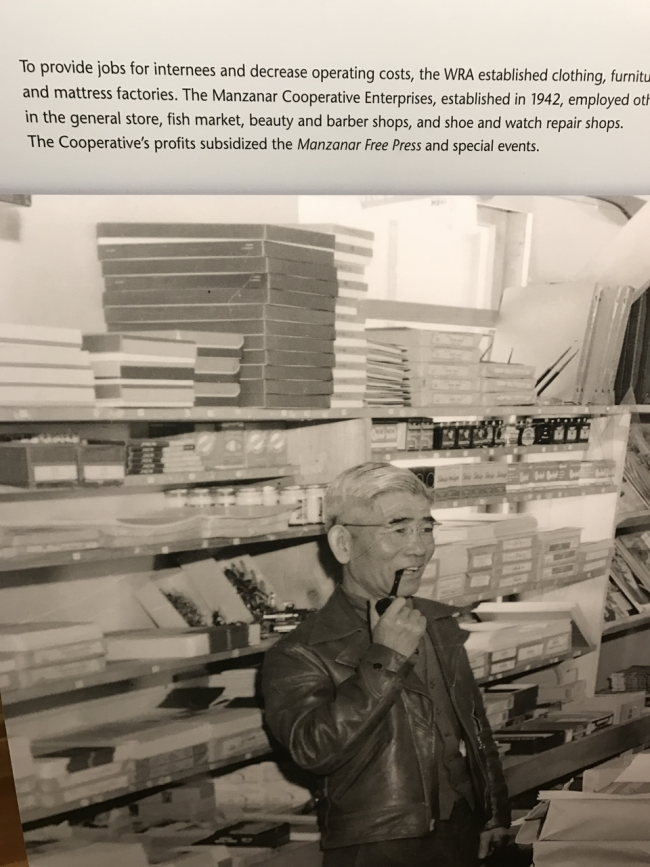

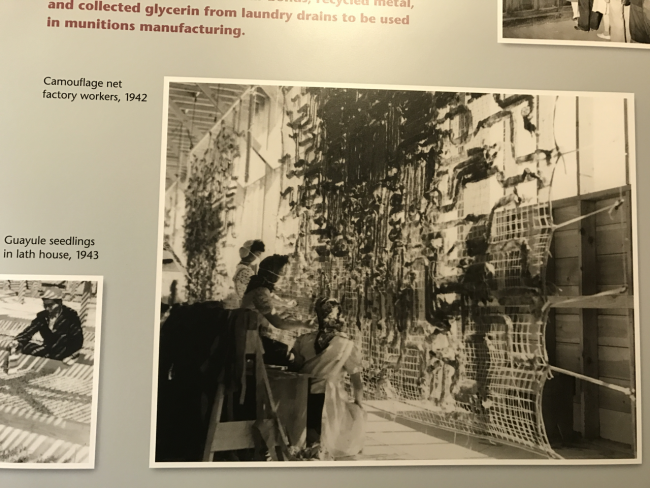

We also saw there the factories that were built, built by Japanese who had been evicted from their homes and transported away from civilization, built so these individuals could voluntarily contribute to their nation’s war effort from behind their barbed wire fences.

The young men at Manzanar, as at every other relocation center, were given the opportunity to enlist. They did so at disproportionately high rates, although doing so was challenging for many: in order to enlist, they had to denounce their allegiance to the Japanese Emperor, something the nissei (born in the US) could not do, as they had no loyalty to denounce–they were American citizens, and had no political ties to Japan. The question was equally troubling for issei, born in Japan but immigrants to the US, because as Japanese citizens living in America, denouncing the Emperor would mean they could never return to the land of their birth, and despite their willingness to fight for the US, that was a difficult line for many to cross. Eventually, the question was re-worded in a way that made it simpler and clearer to answer, without asking enlistees to claim or deny loyalty they did not hold, and thousands joined the 422nd Infantry, one of the most decorated units in World War II.

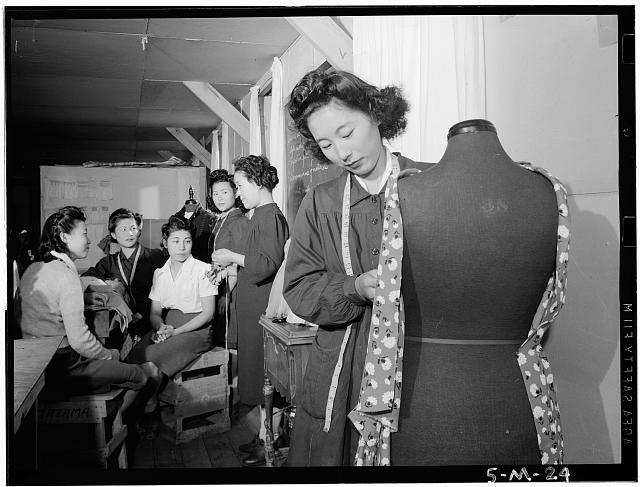

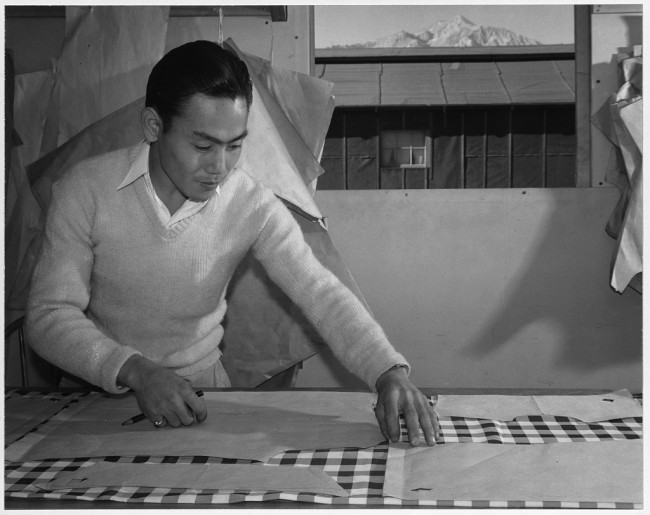

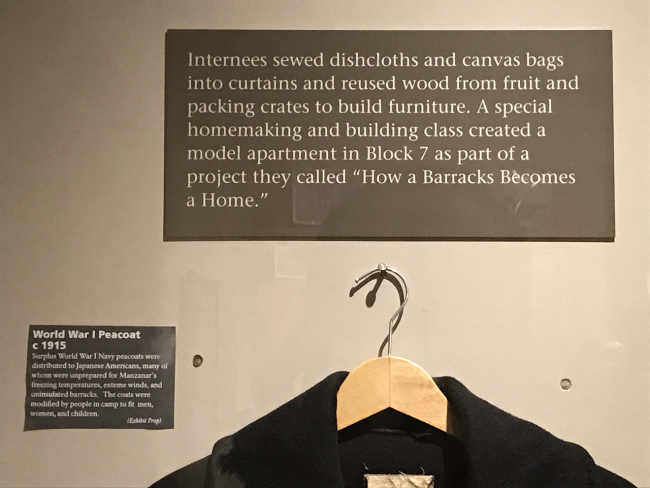

Back at the internment camps, women and men worked behind the scenes to weave camouflage nets for the army and to sew uniforms. Alongside these factories, small cottage industries sprang up–tailors and seamstresses from their prior lives began to offer their services to the families inside the barbed wire and create clothing for them. According to one source, one popular shop took in 220 orders a week, all sewn by hand until machines became available in 1943. Residents of the camps refashioned World War I surplus garments into fashionable clothing, transforming pea coats and men’s shirts into dresses, dress shirts, slacks and skirts for families to wear.

Having seamstresses inside the camps was essential not only for providing adequate clothing, but for basic necessities. It took a full three months after the arrival of the buses before shower curtains could be sewn to allow internees to bathe in privacy–as many as FIFTY DOZEN to ensure that the common complaint that the communal showers lacked privacy could be addressed.

Eventually, seamstresses in the camp would also produce dish towels and aprons for the mess hall staff, and mailbags for the internal mail service. They even made smocks for barbers.

Sewing in the camps served other purposes, too. It allowed the culture and identity of these families to continue. When they arrived, they had no idea how long their incarceration would last–even if it would ever end. The attempts of these families to bring beauty and tradition and a sense of belonging was essential to getting them through the years that would follow.

It also allowed them to build trust and lasting friendships. While all but a very few* of these families was Japanese in origin, they were mostly strangers to one another, and forced to start over building networks and relationships. The ability to create small gifts and tokens in a place where every resource was appallingly scarce offered them an important link to one another.

I am tremendously grateful to the National Park Service for creating a memorial for the hardships that the internees endured, but even more than that, I am grateful for the snapshots of the lives they lived while inside the fences. Many of the women and men who arrived at Manzanar did not know how to sew. They learned while they were there–for work or for recreation or for connection and community. For all those reasons. And sewing was something that gave them meaning and purpose and relationship when all that had been taken from them.

In a very real and practical way, sewing tied a large group of strangers together into a community. Tensions still ran high, fights broke out, and life was difficult. But there was something tangible in sewing that improved their time together and that leaves a legacy for us today.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, acknowledging that the United States government had acted against due process and that the internment centers were unconstitutional. It formally apologized for Manzanar and the other camps, and paid financial restitution to every family that resided there. It took ten years of congressional lobbying by Japanese American groups to gain approval for the act.

Sewing was not ancillary to the events of Manzanar. It was not an afterthought or a footnote. It was central to the experiences of the people who lived in the camps. It was a skill that was brought with them from the outside, something that had value to those both within and beyond the fences. It was an activity that made use of the time they had once their homes and jobs had been taken from them, a way for them to be useful again themselves. It was a connection to the war effort, a partiotic activity that allied them with the nation they called home, working on American soil for American soldiers. It was a community they built amongst themselves, a means of finding security and interdependence with others who shared their circumstances, a method of making something beautiful from an uncertain future.

Sewing creates the world around us, in no small way, every day–in wartime and in peace. It is not a secondary part of our days, or a secondary part of our lives. It is literally the thread that ties us together. Manzanar is a painful reminder of this beautiful truth, and remembering the lives that were lived there gives power to the magic that your needle wields. I am grateful that this part of our history is memorialized, and is shared. I was deeply affected by our visit there, and startled by how moved I found myself of looking at images of women sewing, women who but for time and circumstance, could have been me.

I am grateful for the seamstresses of Manzanar, unsung Great Women of Sewing.

We are all seamstresses. We sew the world, together.

Many of the images in this post were shot by Ansel Adams on a visit to Manzanar. You can see a teacher’s lesson plan for using these images, and access full-size files with educational copyright permissions, here. Other images are direct from the National Archives, here. All other photos were taken during our recent visit to the National Historic Site in California, where honorable American citizens insisted that the words “concentration camp” be used to give weight to the sacrifice of the families who lived there, despite political pressure to tone down the language of the signs at the site.

*One of my favorite stories from the National Monument displays was of a white American wife of a Japanese-born husband, who on learning that her husband and son would be sent to Manzanar and that she wouldn’t “have” to go, flat out refused to be left behind. Over the course of the days before the buses left, she repeatedly packed her bags only to have them rejected by the authorities, as she was not Japanese. They finally allowed her to accompany her family, and she lived with her husband and son at Manzanar until their release in 1944, stating that if they were going, she was going, and the government wasn’t going to keep her out.

sarah

August 18, 2017 at 8:55 pmamazing post and story! thank you for the work you did to tell it. 🙂

Deborah

August 18, 2017 at 9:11 pmThanks so much, Sarah! I can’t believe I had never known about Manzanar until I was an adult, and am so glad I was able to share it here and with my family this year. I hope more of us see this part of our history, so we can avoid repeating it in the future. Thanks for reading!

Daisy

August 19, 2017 at 10:07 amI remember reading Farewell to Manzanar in an English class in high school in the late 80s and being shocked that this had happened — and that not a single one of my history classes had ever mentioned it.

Deborah

August 24, 2017 at 8:40 pmI mentioned it to my husband when we were planning our road trip in California, and he had still never learned of their existence–like, he said it sounded vaguely familiar, but it wasn’t until we were there that he fully realized what we were talking about. And this is a very smart man with both a military background and a law degree! It should be part of the curriculum in our schools, so that we’re reminded. Thanks for reading!

Sabrina B.

August 23, 2017 at 2:41 pmThank you so much for sharing this!

Deborah

August 24, 2017 at 8:38 pmThank you for reading!

Alli

August 24, 2017 at 7:38 pmThis was a lovely post!

It’s not your fault, but I was really shocked to learn that some Americans don’t know about the Japanese internment camps! My grandfather was sent to one, and I just assumed that all Americans would at least know that they existed. It’s kind of terrible if it’s not even mentioned in American history class…

Deborah

August 24, 2017 at 8:38 pmIsn’t that appalling? I was nearly 30 when I first learned of them, and have rarely met anyone without a direct family connection to the camps who was even aware of their existence. Seems hard to avoid repeating a mistake if we don’t learn about it. 🙁

Michele

August 27, 2017 at 10:26 pmThank you for this post. It’s an important part of American history and needs to be remembered.

Deborah

August 28, 2017 at 12:19 pmThank you so much for reading! It’s such a powerful topic, and has been omitted from so many curricula. It makes me heartsick, but it’s important that we remember.

Marina

October 2, 2017 at 12:17 amDeborah please continue to post these type of “educational” posts in addition to your hilarious remarks in your adventures of knitting and sewing. I really like the way you write and educate. I look forward to the day Americans learn the real truths to how this country came into its own. We not only have heart wrenching truths but amazing and heart warming stories. Thank you.

Sheridan

November 30, 2017 at 7:38 amWhen I was much younger the State of California started ripping the camp down and demolished most of it intending to hide its existence forever. Smarter heads prevailed. The Japanese interned there were forced to sell everything, in particular, they had to sell their land “dirt cheap,” now some of the most expensive land in the world. In the current political climate this could happen again.

Jim C.

July 31, 2018 at 11:18 pmI’m glad you mentioned this. Yes, much of the camp still remained standing until the late 70s. I clearly remember seeing it along 395.

What happened is that the Army suddenly tore it down during the late Carter years in fear of it remaining a visible monument. Apparently Carter was furious — it was done quickly and on the sly, as a political move.

Most people don’t realize this happened — the books and websites all say that Manzanar was dismantled after the war or just faded away to the elements. But no, it was still there for many years. And very sad and awful looking.