Stephanie Kwolek isn’t the first name that springs to mind when you think “famous seamstress.” But her scientific contributions have made more impact on our world that you might think–and it all started with a sewing machine.

Born in 1923, Stephanie Kwolek was the daughter of a scientist father and a seamstress mother. While her mother never sewed professionally, she did pass on a love of textiles and fashion to her daughter–in fact, Kwolek said at one point that her mother hoped she would pursue fashion as a career when she left high school. Kwolek was, in her own words, “a very creative child…I watched my mother sewing and making patterns. I imitated…what she did..I remember lying on the floor and drawing, making costumes for these paper dolls. [W]hen I was slightly older, then I made actual clothes from fabric.”

Kwolek’s mother passed on that most basic love of creativity, the satisfaction that comes from the finished product that springs from our own hands: “I used her sewing machine when she wasn’t around; it was fun, and it was creative, and it gave me a great deal of satisfaction.” Combined with her father’s love of botany and their shared garden, this exposure to sewing had a deep influence on Kwolek, as did her time in a one-room schoolhouse in her early years.

Kwolek’s academic skills earned her a scholarship to study biology, but she still thought that she’d end up a fashion designer. In an interview, she says that people in the scientific community seemed to respond positively to her work, and kept inviting her to present papers and research, and she was flattered and enjoyed the pursuit, so she continued. It wasn’t until later, when she’d finished her undergraduate degree and was considering going to medical school, that she began her career in chemistry in earnest.

She went to work for DuPont, despite the fact that she never anticipated spending her entire career with the company. She immediately began doing research in the lab where DuPont had created the world’s first synthetic fiber: nylon. Said Kwolek later, “Eventually the work became so interesting, and I had the opportunity to make discoveries, I made up my mind that I would stay with the work that I was doing, particularly since I found it very satisfying.”

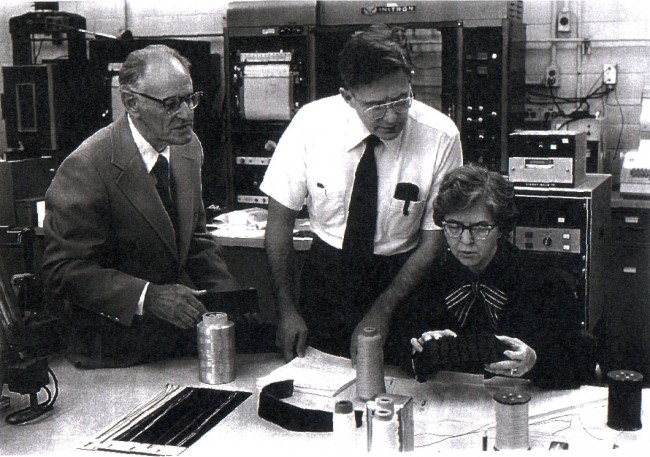

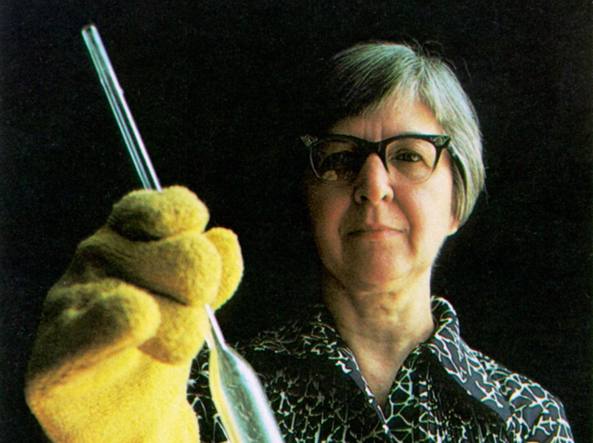

As it happens, Stephanie Kwolek, this accidental scientist with a background in textiles, was assigned in 1965 to a DuPont team seeking a new fiber to replace steel wire, a task brought about by the looming gasoline shortage: lighter tires equals better fuel economy, and lighter tires require something other than steel wire. Kwolek and her team were working with extended-chain polymers, which are spun like cotton candy into fiber. The man working the spinneret, which took the liquified polymers and made them into strands, refused to work with the solution Kwolek produced at first, saying that her solution was too thin and cloudy to spin successfully, but in the end acquiesced–and soon learned that Kwolek had invented what would become known as Kevlar.

Kevlar, five times as strong as steel and vastly more lightweight, is best known for its use as body armor–highly valued by police, military and even journalists in war-torn areas around the world. It’s also used in hundreds of everyday items, from gloves to roads to, yes, tires.

Bulletproof vests work by layering Kevlar fibers, which work with a little give to “catch” the bullet and offer wearers 40% more protection over similar garments, such as helmets, made of steel. I love that Kwolek, who understood fabric and textiles, had a major hand in revolutionizing the way we think about the properties of fibers and what they are capable of doing. Kevlar today is used even in fiber optic cables, and so Kwolek’s work is accessible to us now through the internet–which travels along and in some places is made possible by those very cables. In fact, if you’ve ever completed the “rope trick” in a high school chemistry class, you’ve benefitted from Stephanie Kwolek’s contributions to science and sewing very directly.

I doubt that Stephanie Kwolek ever regretted not spending her career in the world of sewing. Her life story indicates that she thirsted for research and experimentation, and that she valued her ability to offer something lasting to others through her work–Kevlar has done that. I also doubt that without a background in sewing and textiles, her scientific experience would have led her to create what she did. Seems to me, after years of working with various fabrics and playing with shapes and weaves and weights and drapes, one becomes much more willing to trust the fiber and see potential where you might not otherwise. Kwolek didn’t listen to her lab colleague, who was sure her extended-polymer solution was too watery to spin into a useful fiber, or reject her own solution because it didn’t meet the expected parameters. She trusted her gut, and spun something revolutionary.

She may have only indirectly entered the fashion industry with the bulletproof vest, but she made a greater impact than any of the bullets Kevlar ever blocked. According to one source, with her discovery, Kwolek “challenged the concept of what material is capable of.” Kwolek said later in life, “I don’t think there’s anything like saving someone’s life to bring you satisfaction and happiness.” She is one of a very few women to be awarded the Perkin Medal, the National Medal of Technology, the DuPont Company’s Lavoisier Medal, and to be inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Here’s to Stephanie Kwolek, a Great Woman in Sewing.

Sabrina B.

May 18, 2016 at 9:04 amWhat a great story! One thing that science and sewing have in common is the creativity element, something that many non-scientists do not appreciate about science (but that I know you do). Materials science, in particular, has similarities to the kind of creativity we find in sewing since the goal is to produce something tangible (rather than simply creating ideas, as in my field of biology). I find the tangible element of sewing offers a nice counterweight to the intangible elements of my day job.

Deborah

May 23, 2016 at 9:41 amI absolutely agree. I spent so much time as an archaeologist working with theory and intangible ideas, putting pieces together but not actually MAKING things, that I can understand more clearly now why I became so enamored of sewing while I was in graduate school. Sewing is totally a whole-brain activity–which must be why we keep coming back to it, right? 🙂

Kathie

May 19, 2016 at 7:37 amGreat post. Thanks for sharing your research.

Ruth

May 19, 2016 at 10:58 amI had never heard of Stephanie before, but now I’m intrigued. Off to see what else there is to know about this fascinating woman. (I’m curious like that.)