The word “dressmaker” seems to speak differently to me than the word “seamstress.” Almost as if I think a dressmaker is someone who sews for herself but a seamstress sews for others? Historically, I’m not sure that’s true, but in this case, the case of Ann Lowe, it seems to be.

Wedding dresses lean into the iconic by their very nature: the bridal gown is a garment whose sole purpose is to carry a human across the boundary between one identity and another. People put a lot of weight on a wedding gown, embedding a great deal of meaning into each seam. Marriage is a sacrament, an outward sign of an inward transformation, that in every culture worldwide stands as a unique bond between individuals, a leap into faith that the future will hold, ultimately, joy and reward. We hold weddings in public, not because we need the approval of others, but because the public nature of a wedding brings to the delicate, intimate bond formed between bride and groom the weight of consequence and gravitas. The bridal gown is an outward signifier of all those invisible truths, and holds a unique place in culture as a result.

This gown, I mean. THIS gown is infamous. It carries not only the weight of the wedding day itself, and the identity of the bride, but also the tragedy of the lives that were tied together that afternoon, and the scandal of the stories they lived.

It was designed by a woman named Ann Lowe.

Ann Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama in 1898. Ann’s mother was a dressmaker who died suddenly when Ann was only 16. Still in high school, Ann took over and completed her mother’s unfinished designs on time, including a commission from the First Lady of Alabama in 1914.

She learned early and paid attention, that much is clear: she loved making fabric flowers and embellishing dresses with them, a design element that appears throughout her later work. She was talented enough to be accepted at the prestigious S. T. Taylor Design School in New York City at the age of 19, where she was frequently held up as an example of good technique to her all-white classmates; as the only Black student, Ann was given a separate space in which to sit and work, apart from the other designers.

I think about that a lot, about this woman before World War I, leaving a tiny town in Alabama to head to the Big Apple, knowing she would be intentionally segregated from the other students but driven to attend, all the same. That she must have really, really wanted to learn to be willing to subject herself to those circumstances.

Which is not to say Ann Lowe was more-than-human, or a saint. Not at all. By all accounts, Ann Lowe was a poor businesswoman, and more than one historian has used the word “snob.” She is regularly quoted as saying, “I love my clothes and I’m particular about who wears them…I am not interested in sewing for… social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.” I wonder if that bent toward the American aristocracy came from her boot-strapping youth, her knowledge that these people in power could hold the key to her livelihood.

It also made her overlook the sound business principles that might have created a viable income stream from her formidable talent. Ann Lowe designed for the elite of the Main Line, for wealthy families with political connections. She made unique gowns for debutantes and governors’ wives. She designed and constructed the gown in which Olivia de Havilland collected her Oscar for The Snake Pit. And by all accounts, Ann Lowe died penniless and largely unsung.

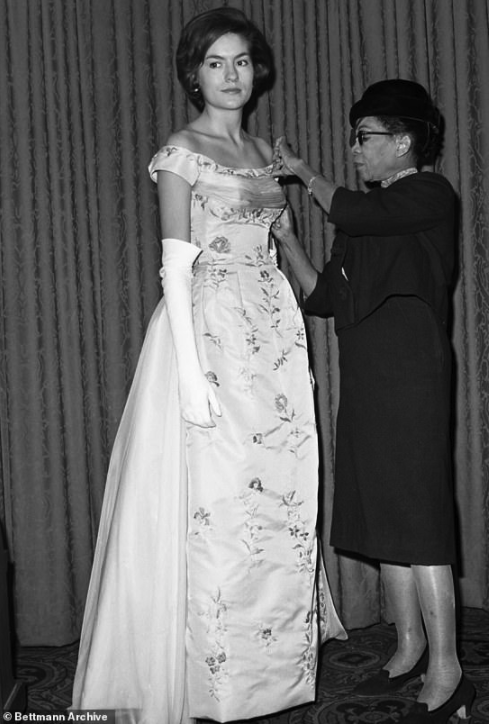

The most famous story about Lowe is the one from the Kennedy wedding. Making all those debutante dresses along the Main Line connected Ann Lowe to some pretty high-falutin’ folk. One of those, Janet Lee Bouvier, came from an old Southern family and had a daughter who was set to marry the junior senator from Massachusetts in a lavish Newport wedding.

The dress may not have even been what Jacqueline Bouvier wanted for her wedding day. She was Cinderella, but it was Kennedy’s father, Joe, who had the final say on the bridal gown. It was to be elaborate, made of the finest silk with trapunto detailing that built up three-dimensional extravagance to surround the bridal couple as they walked down the aisle.

Lowe labored over the dress for weeks leading up to the wedding day. Just hours before she was scheduled to deliver it to Newport for the ceremony, disaster struck: her studio was flooded, and the bridesmaids’ dresses along with the indulgent gown were destroyed.

What was she to do? Losing this commission could mean the loss of her business, her reputation, her connections to the elite of society. So Ann bit the bullet and re-purchased the fabric with her own money, hired additional seamstresses to replicate the labor in a matter of hours that had taken days and days to create, and arrived to deliver the dresses on time.

And this is where the details of the story all agree but didn’t make sense to me for a long while: when Ann Lowe arrived on the doorstep to deliver the gowns, carrying a loss of nearly two thousand 1953 dollars over her arms that came from her own pocket, she was told to go around back and use the colored entrance.

Her reply, according to every report I could find: if she had to use the back door, “I’ll take the dresses back,” and walked right on through the main entrance.

When I have read that quote, over and over, I loved it. I assume that every other writer did, as well. It’s the statement of a woman who has HAD IT with the BS, and isn’t going to take it anymore. But somehow it didn’t track with the other details of Lowe’s story: she’s a snob, so she admires the social set, but she can’t belong to it because she’s Black; she won’t use the back door, so she’s proud, but she spent her own money on the dresses in order to maintain her connection to these families.

Hang on to that dichotomy while we unveil (if you’ll excuse the pun) the rest of the wedding day.

Ann delivered the dresses. They were a smash. The Kennedy wedding is often referred to as the most photographed wedding in American history. The dress itself is on display in the Smithsonian Museum of American History. And the story goes, when asked who designed her gown by Life Magazine, that Jackie replied, “A colored designer did it.”

By all accounts, Ann Lowe was crushed. This was her MOMENT, and the bride erased her from the story.

So when I think about the woman who wouldn’t use the back door, I wonder why she bothered at all. These families talked about Lowe as the “best kept secret,” but a woman who refuses to go in the back doesn’t WANT to be a secret. I wonder if Ann Lowe believed that her sacrifice to deliver those gowns was the moment when it would all pay off for her–and that refusing to use the back door was a sign that she believed she’d achieved real success and recognition.

Had she been white, I have no doubt that would have been the case. But again and again, Ann Lowe’s designs have been minimized or elimiated from the history books. Lists of dresses worn by Oscar winners cite the designer of Olivia de Havilland’s 1947 dress as “unknown.” In 1961, Ann and her team hand-beaded dozens of gowns in a Saks Fifth Avenue commission for the Ak-Ben-Sur fraternity in Nebraska at a significant financial loss, and was never given named credit for her work.

When later Jackie Kennedy made another comment to the press that Ann Lowe felt minimized her, she wrote a letter to the First Lady and let her know; they eventually reconciled and worked together for years, but my instincts tell me that Lowe never forgot that on the chance of her big break, she was reduced to the color of her skin rather than the skill of her needle.

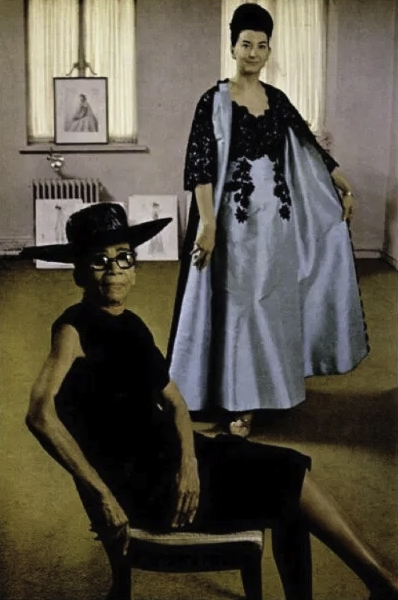

Today, Ann Lowe is recognized not simply for being the first major Black dress designer with a fashion house on Madison Avenue, but for her bold designs that have touched American history. Her gowns are on display in both the Museum of American History and the Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. Her skill with fabric flowers is jaw-dropping. She attended Paris Fashion Week in the 1940s and met Christian Dior, who hailed her skill. She was named Couturier of the Year in 1961, which included the honor of naming her to the Social Register for whom she sewed–you don’t have to watch many Hepburn films to understand just how enormous a thing that was to achieve, for anyone.

In 1963, she was forced to declare bankruptcy.

The story of Ann Lowe is often reduced to one of resilience–which is certainly is. This is a woman who should, by all accounts, have fallen apart and never gotten back up. The town she’s from in Alabama? So tiny that I’ve never heard of it, and I lived there from the age of four. It’s not a big state, and everyone you know knows everyone you know there, so this was a tiny, tiny town she was from. Yet here I’m writing about her, over 100 years later, and her skill with a needle, linking to her creations at the foremost museum of American culture in the world.

She was a Black woman working for white elites in a white-dominated industry, and she was revered by all who enjoyed her work, including her esteemed peers.

Her bankruptcy? Didn’t ruin her. An anonymous donor–rumored to have been Jackie Kennedy Onassis herself–paid her debt and enabled her to continue designing into her late 90s, despite failing eyesight and hearing.

Most articles either celebrate that Ann Lowe overcame circumstances, or they bemoan that she was given so little credit. Much of the writing about her has been in the past year–like, more than 90% of the information available has been published in that time–based on the effects of a single viral tweet. Which makes this a story of a woman who could and should have been given more attention but for the lack of financial resources to get it.

She certainly had the skills. She had the start in the industry. She lacked solid financial advice and bookkeeping to maintain the momentum of her successes. It’s beyond argument that color of her skin prevented her from accessing the resources that could have allowed her to turn her own moxie into an empire; without those, she was constantly struggling, despite her talent.

There is a whole long list of Black designers who created real art with their needles–and their names were forgotten or glossed over, even erased on purpose so the credit could go to someone else. That happens to non-Black designers too, to be sure, but I’d like to ask you to consider: does it happen more to Black designers because the ones doing the erasing think it doesn’t count? or that they won’t speak up? or that they can get away with it because “who’s gonna believe a colored designer made that”?

Ann Lowe was talented and admired. She created art with fabric, and she used it to build iconic works of fashion that we revere to this day. I believe, in her own way, Ann forged ahead through racism and elitism to gain ground for herself and the other Black designers who came after her. Ann Lowe is a Great Woman of Sewing.

Deborah Makarios

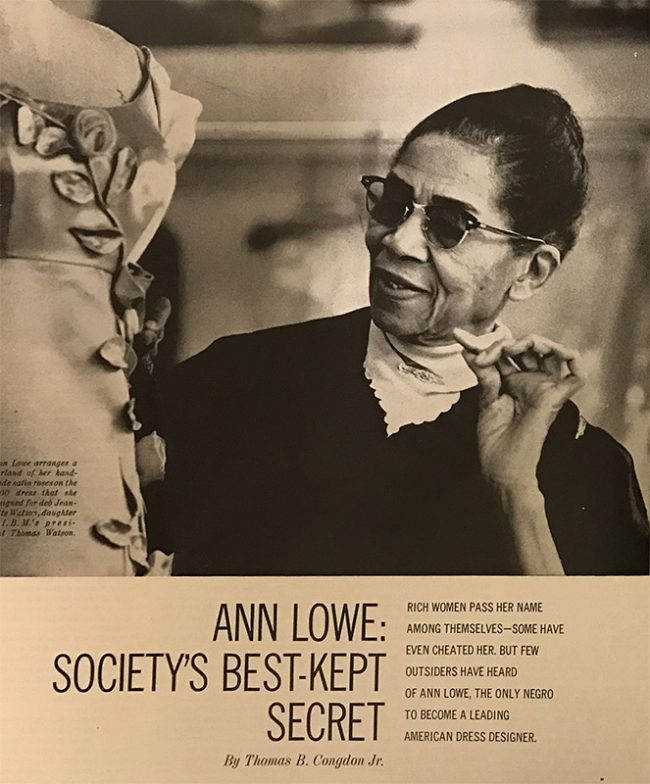

July 23, 2020 at 4:40 amI see the first image describes Ann Lowe as “the only negro to become a leading American dress designer.” Had Thomas B. Congdon Jr. never heard of Elizabeth Keckley?

Deborah Moebes

July 23, 2020 at 9:41 amWell, exactly. Keckley is on my list of names for this series, but I haven’t finished reading her memoir, Behind The Scenes, yet. Fascinating!!

Audrey Workman

July 23, 2020 at 5:53 amThanks for the research, Deborah. This is both fascinating and tragic. Oh, the assumptions, and the blindness! Zora Neal Hurston wrote, “Black women are the mules of the world,” and here’s Ann Lowe proving her right yet again. Both Ann and Zora were compelled to continue creating astounding beauty in the face of adversity, yet both died with no financial wealth. We have systems to change.

Melissa Irvin

July 23, 2020 at 7:21 amThank you for this education, Deborah!! What a remarkable lady Ann Lowe was.

Pam

July 23, 2020 at 9:58 amLOVE this post! Looking forward to more!

Diane Cunanan

July 23, 2020 at 10:43 amWow! Her works are timeless! Thank you for this story of a remarkable talent!

Cecilia G Schermaul

August 21, 2020 at 7:35 pmMy God, we have a lot as a people to be ashamed of… Why are people afraid to say the name of the person who did the work, no matter what the color of our skin.

When I came to this country in 1961, I was so ashamed of the way people of another color (black) were treated. I have never heard of this, it was not the way I was raised, my parents would never have allowed that!

So sad!

Sincerely, Cecilia Gardner Schermaul

Diane Christy

September 1, 2020 at 9:39 pmA couple of years ago, I went to the Tenement Museum on the lower east side of Manhattan. We took the “Sweatshop” tour and learned about the largely Jewish men and women who did piecework at home. The tour guide asked us what we thought was going on the minds of the young women who were sewing fancy dresses for the elite of the city. I spoke up and said they were angry. Angry that they could never afford a dress like they made for someone else, mad they would never attend an event to which these garments were worn. The empathy arose from my own custom children’s clothing business, where I was serving a clientele with whom I did not socialize even though our children went to the same exclusive private school. That insight revealed to me what I was keeping bottled up; having to metaphorically use the back entrance as I served my clients.